A Red-breasted Sapsucker provides a spark of fiery color during the cold, gray of Winter.

On New Year's Eve, while watching a Downy Woodpecker foraging among the branches of this Willow tree, a faint motion, next to the trunk of the tree, diverted my attention. I felt fortunate to spot a Red-breasted Sapsucker (RBSA).

By this time of year, most leaves from deciduous trees have fallen, I expect the sap created in the leaves would normally have already descended to the roots, and that hungry Sapsuckers would have usually switched to feeding on evergreen trees.

However, this old Willow is unique. At some point, probably many years ago, the tree slipped into this horizontal position. The root system must have stayed intact. Not only did the tree survive, it appears to be thriving. It now supports numerous vertical branches, each of which behaves almost like an individual tree. I wonder if this single tree could one day become a grove of genetically identical trees.

This tree resides, or maybe I should say reclines, on the shore of Duck Bay, next to the path to Foster Island, in the Washington Park Arboretum.

Surprisingly, this tree retained numerous leaves, even in early January. The presence of the leaves, the Sapsucker, and the obvious moisture around the fresh holes, indicated that the sap was still flowing.

The Arboretum Tree Map says this tree is a "Salix sp." I understand that to mean it is one of more than 300 species of willows in the world, but which one is uncertain. I faintly remember a gardener suggesting that this tree might be a Salix alba. The word alba means white, which is apparently a reference to the light color on the underside of the leaves. Salix alba is a willow species that originated in Europe and Asia.

After a while, the Sapsucker moved to a second set of holes on one of the other "trunks" of the tree. The Downy Woodpecker moved towards the sap wells that the Sapsucker had just abandoned. I suspect the Downy was hoping to find insects caught in the sweet, sticky substance. Immediately, the Sapsucker moved back to defend its investment in the original set of holes.

It is interesting to note that there are only four Sapsucker species in the world, and they all live in North America. I suspect that trees from other areas in the world, like the Salix alba, may have been less motivated to develop thick bark, in part, because in their original range, they never encountered Sapsuckers.

To the east of the Cascade Mountains in Spring you can find Red-naped Sapsuckers (RNSAs) and Williamson's Sapsuckers (WISAs). Further to the east and up into Canada and Alaska are the Yellow-bellied Sapsuckers (YBSA) in the Spring.

The author of this post, about YBSAs, suggests that when they begin working on a tree the YBSA drills an exploratory set of horizontal holes. The idea is that they are looking for the highest volume of sap. When they find the desired sap flow they begin drilling their way up the tree, creating vertical sets of holes. Multiple sources imply that YBSA and RBSAs behave similarly. Perhaps, this behavior applies to RBSAs too i.e. the horizontal holes are exploratory and the vertical ones are maximizing their mining effort. I can't say I have documented the behavior, but it will be interesting to pay closer attention to how they work.

This Sapsucker did seem to feed primarily near the tops of the vertical columns of holes. That makes sense especially if it was feeding on the sap created in the leaves and flowing down to the roots. This sap travels down via the phloem. So it can be safely stored for the winter without freezing. During, the first week or two in January, I found what appeared to be this same Sapsucker, in the same tree, multiple times.

I wonder if the Sapsucker knew that the cold snap was coming. Did it target the tree with the leaves? Were the leaves like little flags blowing the breeze, sending a signal that the sap was still flowing? In any case, the Sapsucker was clearly taking advantage of this last source of deciduous sap.

RBSAs can also drill deeper holes to access the water and minerals that flow up from the roots via the xylem. The Xylem is a bit deeper in the tree than the phloem so the holes require different depths. However, with cold weather approaching, I would expect the tree would not be pulling up water that could potentially freeze and shatter the tree.

On January 3rd, toward the end of the day, the Sapsucker left the tree and flew west across Duck Bay. I could only think of one other tree, in line with its flight path, where I had seen a RBSA before. I figured it was a long shot but decided to check out, just in case.

To my surprise, it worked. There was a RBSA in the tree. But was it the same bird?

.

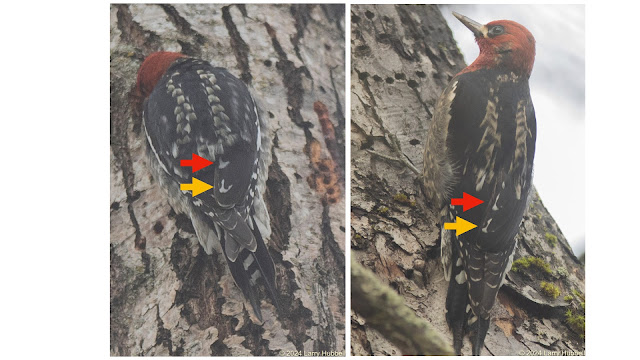

After the RBSA moved to the opposite side of the trunk, these photos were taken just 7 seconds apart. They are both of the same bird.

Do you notice any differences in the feather patterns between the two photos?

The white vertical bar, along the side of the bird, is very obvious in the second photo but mostly hidden in the first one. The point is that birds can appear to be in pretty much the same position but still change the arrangement of their feathers (particularly wing feathers) and their appearance.

This white bar covers the upper portion of their primary wing feathers. Whether we see it or not is dependent on the way the bird happens to be holding its folded wings. So, even though a wing bar is an obvious field mark, it is not be a useful way to distinguish one Sapsucker from another.

A couple of years ago, I did notice a small set of white-tipped feathers on the backside of RBSAs that seem to be very consistent, often visible, and perhaps unique to each bird. (Click Here to read my first explorations along this line.)

The bird on the left was photographed in the willow next to Duck Bay. The one on the right is the bird I saw further to the west. Do you see any markings that make you think they may or may not be the same bird?

I believe the red arrows are pointing to the tip of the innermost tertial, i.e. the innermost wing feather that is closest to the body, in this case, on the right wing of each bird. The yellow arrows point to the tip of the next tertial, i.e. one feather further out from the body of the bird. The white tips on the first bird look somewhat similar to the letter "U" while on the second bird, they look more like the number "1". The point is these markings are different for each of the birds.

In Birds of the World (BOTW), referring to RBSAs is says, "...the distal portion of tertials variably white along shaft and at tip." (Citation Below) This documented variability is what helps make the case for me that these are two different birds.

I think it helps that the location of these inner feathers protects them from wear and tear. Hence, the white tips are less likely to change shape between molts. Plus if they do not get much wear they may not need to be replaced during every annual molt.

These white-tipped feathers could look similar on some RBSAs. However, when the tips look distinctly different, at nearly the same time, I think it is logical to conclude they are two different birds.

On the other hand, when these feathers look alike, on birds found at the same location, over a week or two, it also seems fair to assume we are probably looking at the same bird.

The photos above, for example, were taken ten days apart and both birds were in the reclining Willow next to Duck Bay. Even though the angle is slightly different and the wings are held a bit differently the white tips of the visible tertials look remarkably similar. (I also have additional photos that show these same patterns on the Duck Bay Sapsucker.) As the second photo illustrates, depending on how the bird holds its wings, not all four feather tips are visible all of the time.

Even though I believe this is the same bird, it is interesting how the other lightly-colored feathers, higher on the bird's back, look somewhat different in each photo. Trying to identify individual birds by their markings is certainly not foolproof, but it is a fun way to challenge ourselves to learn more about our wild neighbors.

Sadly, for the Sapsucker, last week some truly cold weather came to Duck Bay. I have not been able to locate a RBSA since then. However, a friend in Ballard did see one near his house this week. It is reassuring that they haven't all gone south. However, it does raise the question, How do they survive the bitter cold?

Overall, many probably survive by migrating south. However, if you watch eBird's weekly dynamic map of sightings it is obvious that they migrate in two different ways. Some migrate north to south in the Fall, like other species, while others migrate east to west i.e. vertically.

In the Spring, much of their nesting takes place in the mountains of British Columbia and Washington. However, in the Winter, many RBSAs move to a lower elevations, instead of going south. Lucky for us, there are sightings of them year-round in the lowlands of Western Washington.

I suspect that on cold Winter nights, those who spend the Winter here may use old nest holes as roosting cavities. Hopefully, the surrounding wood of a dead snag provides adequate insulation. Nonetheless, they almost certainly need to find food during daylight hours to secure enough energy to make it through the cold nights. I wouldn't be surprised to learn that some of you had RBSAs visiting your feeders during the cold snap.

Recommended Citation

Walters, E. L., E. H. Miller, and P. E. Lowther (2020). Red-breasted Sapsucker (Sphyrapicus ruber), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (A. F. Poole, Editor). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.rebsap.01

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

By the way, the Arboretum, including the trees, birds, insects, nest sites, fruit, flowers, squirrels, salamanders, rabbits, pollinators, butterflies, dragonflies, bees, frogs, and to some degree even the coyotes, otters, beavers and the occasional deer, thrive because of private support.

Both the City of Seattle and the University of Washington contribute funding to the Arboretum, however, significant private support is required to keep it functioning. The most enjoyable way to support the Arboretum is via the Annual Opening Night Party. (If you sign up soon feel free to request a seat at my table. If the timing works out, we will have a chance to enjoy a delightful dinner during the birthday celebration.)

Opening Night Party 2024

Celebrate the Arboretum's 90th Anniversary at the

Botanical Birthday Bash

Tuesday, February 13, 2024

5 - 9 pm

With a preview of the Northwest Flower & Garden Festival!

A Benefit for the Washington Park Arboretum (1934 - 2024)

~~~~~

You'll enjoy:

An opportunity to purchase and bid on unique and enticing experiences

(Like a hosted Raptor Road Tour around the Skagit area)

An exclusive preview of the Garden Festival before it opens to the public

Hosted social hours with drinks and appetizers

Seated dinner

The 90th birthday toast and celebration!

~~~~~

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Have a great day on Union Bay...where nature lives in the city and Black Birders are welcome!

Sincerely,

Larry

Each of us, who breathes the air, drinks water, and eats food should be helping to protect our environment. Local efforts are most effective and sustainable. Native plants and trees encourage the largest diversity of lifeforms because of their long intertwined history with our local environment and the local native creatures. Even the microbes in the soil are native to each local landscape.

I hope we can inspire ourselves, our neighbors, and local businesses to respect native flora and support native wildlife at every opportunity. I have learned that our most logical approach to native trees and plants (in order of priority) should be to:

1) Learn and leave established native flora undisturbed.

2) Remove invasive species and then wait to see if native plants begin to grow without assistance. (When native plants start on their own, then these plants or trees are likely the most appropriate flora for the habitat.)

3) Scatter seeds from nearby native plants in a similar habitat.

4) If you feel you must add a new plant then select a native plant while considering how the plant fits with the specific habitat and understanding the plant's logical place in the normal succession of native plants.

***************

Keystone native plants are an important new idea. Douglas Tallamy, in the book "Nature's Best Hope ", explains that caterpillars supply more energy to birds, particularly young birds in their nests, than any other plant eater. He also mentions that 14% of our native plants, i.e. Keystone Plants, provide food for 90% of our caterpillars. This unique subset of native plants and trees enables critical moths, butterflies, and caterpillars that in turn provide food for the great majority of birds, especially during the breeding season.

Note: Flowering plants and trees, i.e. those pollinated by bees, are also included as Keystone Plants.

This video explains the native keystone plants very nicely:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=O5cXccWx030

The Top Keystone Genera in our ecoregion i.e. Plants and trees you might want in your yard:

Click Here

Additional content available here:

https://wos.org/wos-wp/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/Native-Plant-Resources-10-7-22.pdf

******************

In the area below, I am displaying at least one photo with each post to help challenge us to know the difference between native and non-native lifeforms.

Which of these is a native Alder and which is not?

This next photo provides a hint about the common name of our native Alder.

Scroll down for the answer.

******************

Red Alder: Our native Red Alder tends to have the more pointed leaf. The European Alder, which can also be found in the Arboretum, has a much more "rounded" leaf.

Did you notice the holes in the native Alder leaves. These are a wonderful sign that a native life form, possibly caterpillars, know how to feed on this tree. Indirectly, this turns the tree into a food source for a wide variety of young birds.

*****************

The Email Challenge:

Over the years, I have had many readers tell me that Google is no longer sending them email announcements. As of 2021, Google has discontinued the service.

In response, I have set up my own email list. With each post, I will manually send out an announcement. If you would like to be added to my personal email list please send me an email requesting to be added. Something like:

Larry, Please add me to your personal email list.

My email address is:

LDHubbell@comcast.net

Thank you!

*******************

The Comment Challenge:

Another common issue is losing your input while attempting to leave a comment on this blog. Often everything functions fine, however, sometimes people are unable to make it past the robot-detection challenge or maybe it is the lack of a Google account. I am uncertain about the precise issue. Sadly, a person can lose their comment with no recovery recourse.

Bottom Line: If you write a long comment, please, copy it before hitting enter. Then, if the comment function fails to record your information, you can send the comment directly to me using email.My email address is:

LDHubbell@comcast.net

Sincerely,Larry

Parting Shots: